On 1 July 2016 millions will remember the Battle of the Somme. Although the bombardment began a week earlier the 1 July is seen as the day the battle commenced. My own personal connection to the battle is not through a family connection but in the journey I made to trace what happened to the lives of the boys from the school I attended in two world wars.

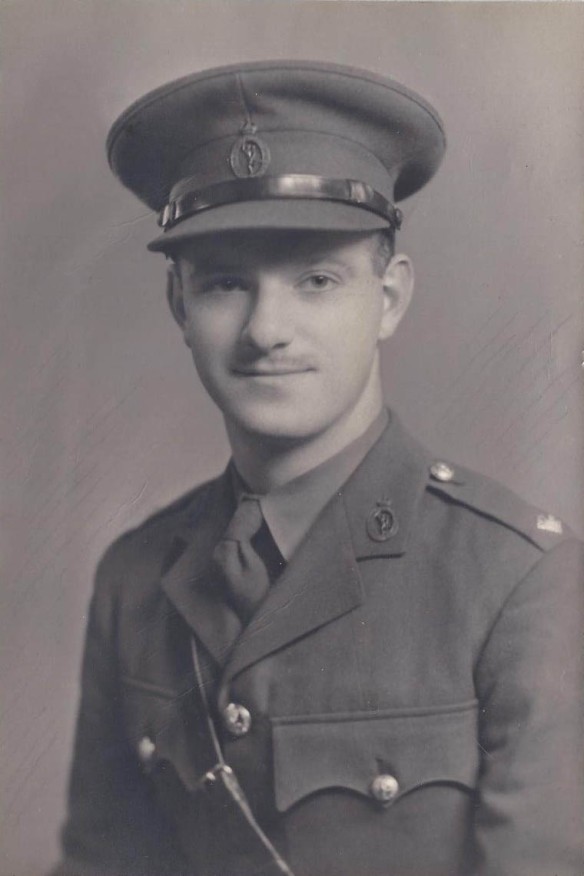

Ronald Grundy

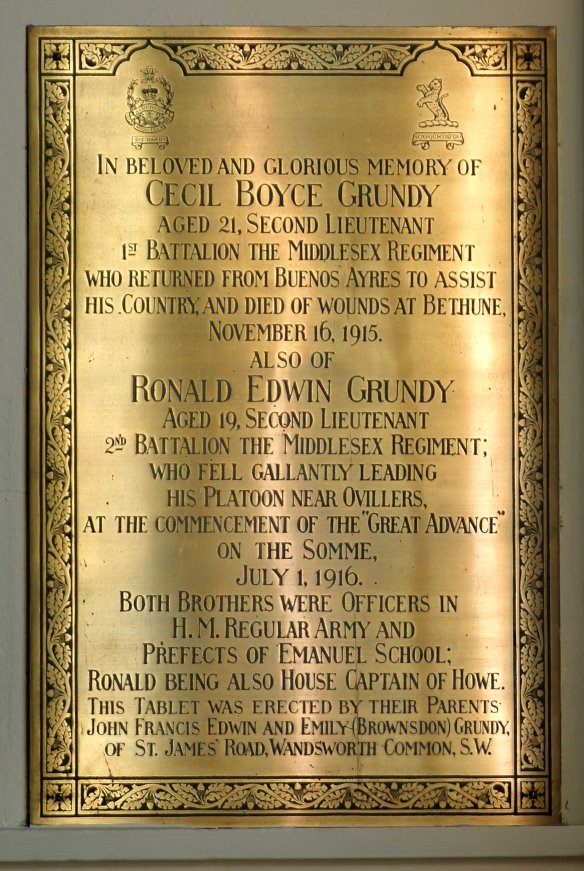

One young man’s short life resonated with me during that discovery. Ronald Grundy attended the same school as I did but he also lived a few minutes walk from my home. He had taken a similar journey to me but we were separated by a century. Ronald grew up playing on Wandsworth Common as I did. He sat in the same school chapel pondering upon the greater meaning of life. Yet at 19 he faced a far greater test.

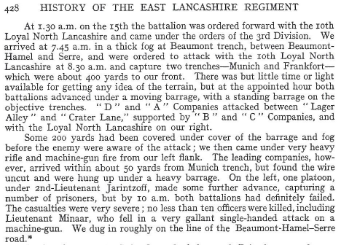

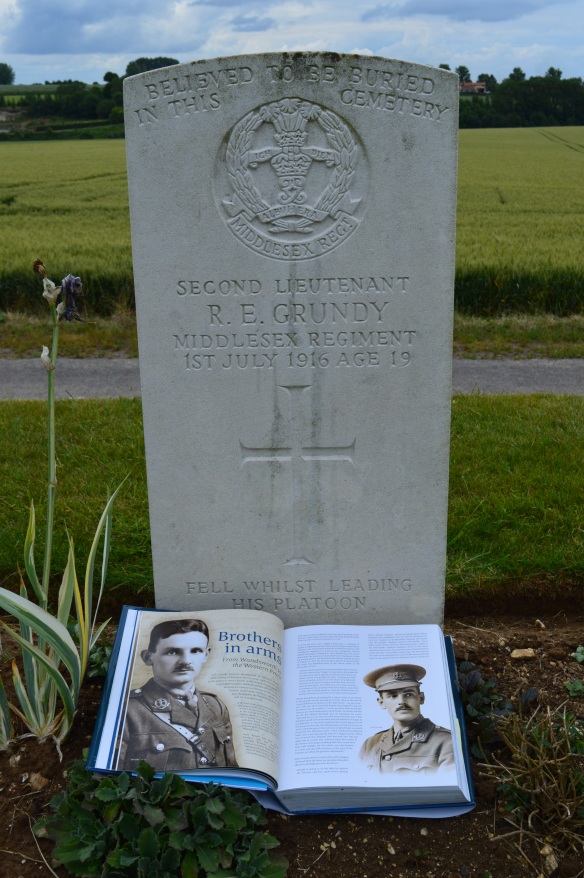

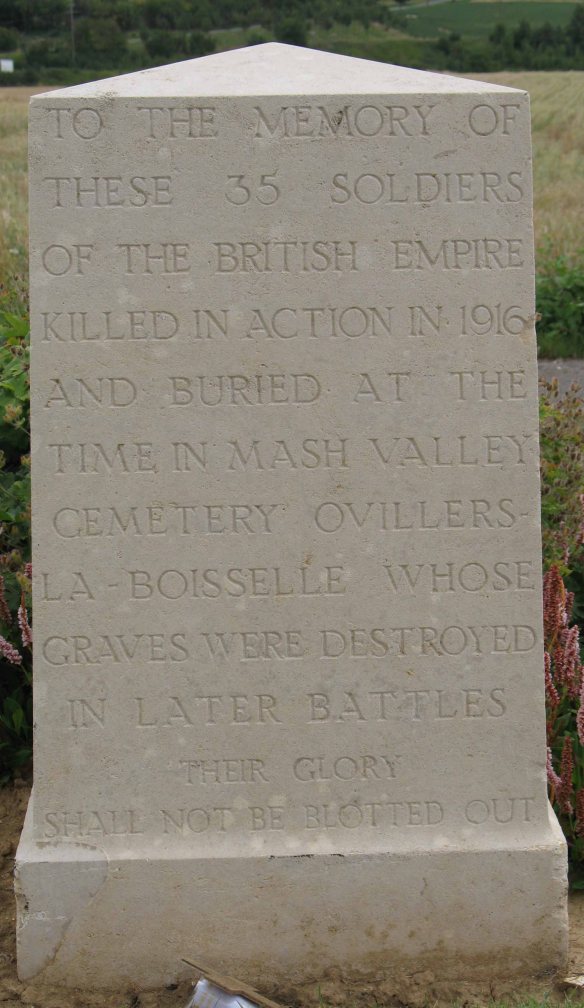

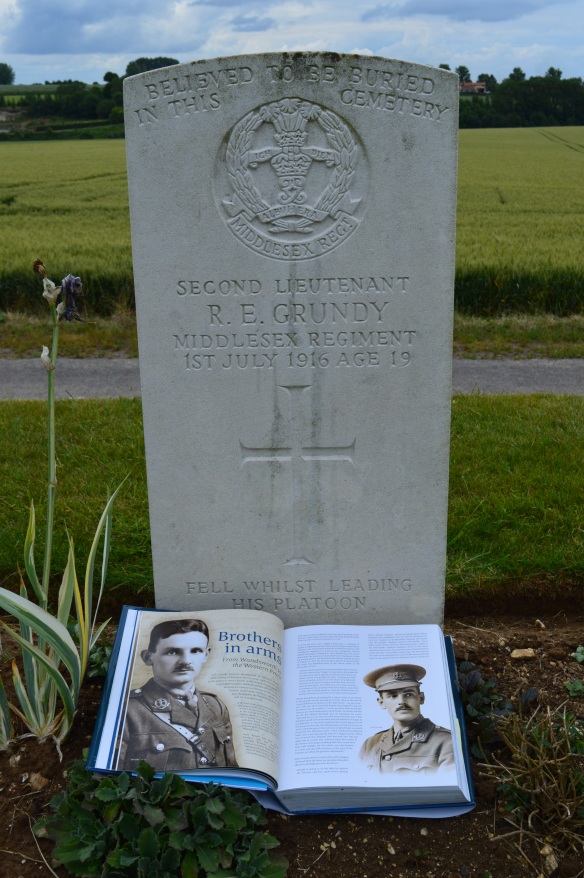

On a July day in 2010 I set out to find out what had happened to him. I visited the Commonwealth War Graves Commission cemetery of Ovillers where a gravestone bears his name. Standing among a line of gravestones separated from the vast majority they face is a stone inscribed with the following words, ‘TO THE MEMORY OF THESE 35 SOLDIERS OF THE BRITISH EMPIRE KILLED IN ACTION IN 1916 AND BURIED AT THE TIME IN MASH VALLEY CEMETERY OVILLERS-LA-BOISSELLE WHOSE GRAVES WERE DESTROYED IN LATER BATTLES: THEIR GLORY SHALL NOT BE BLOTTED OUT’. In the flowerbed beside this stone were bees busily seeking out pollen on a fine summer’s day, far removed from the intensity of battle that the names on those graves once knew. As I stood there that afternoon I wondered in what ways Ronald’s life had ‘not been blotted out’ by time and how he had been remembered?

Memorial Stone, Ovillers British Cemetery

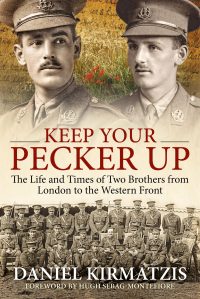

The story is one I have written about in a book I am hoping to publish as an ebook later this year but on the anniversary of the Battle of the Somme I wanted people to remember the sacrifices Ronald and the men of his battalion made that morning.

I have written about Ronald and his brother Cecil before and you can also listen to their story here from a BBC World War One episode on the boys from Emanuel School, Battersea.

1 July 1916

On the morning of 1 July 1916 the Battle of the Somme began in full. For Ronald it would last all but eight minutes. By the end of the first day of the Battle Ronald was one of 19,240 British servicemen who were killed in action or died of wounds. It was the worst day in

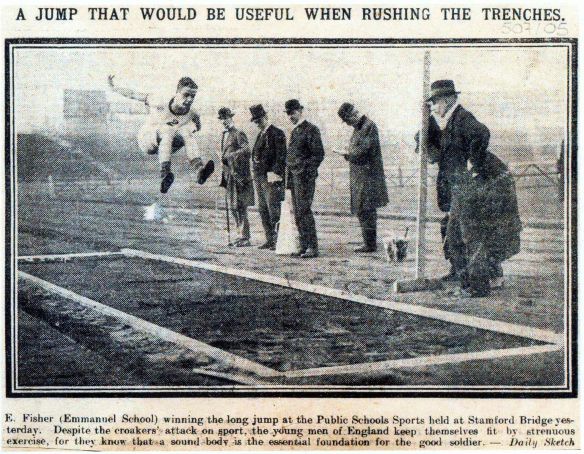

British military history. The tragedy felt the more from the fact that over half of the 120,000 infantrymen who fought on the opening day were volunteers – members of Kitchener’s New Army. This does not mean, however, that they lacked foreknowledge of their potential fates. Those who had been members of their school’s cadet or officer training corps and who overwhelmingly were promoted to infantry officers, had been versed in the classical and medieval language of sacrifice from their headmasters’ assembly and prize day sermons and so were made aware what was at stake in this titanic struggle. But the shooting range at home was unfortunately ill preparation for facing the reality of the nightmares they fell into.

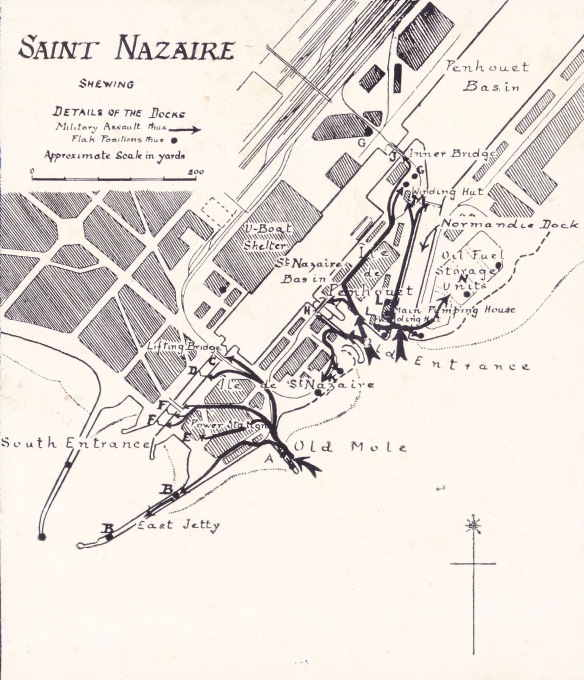

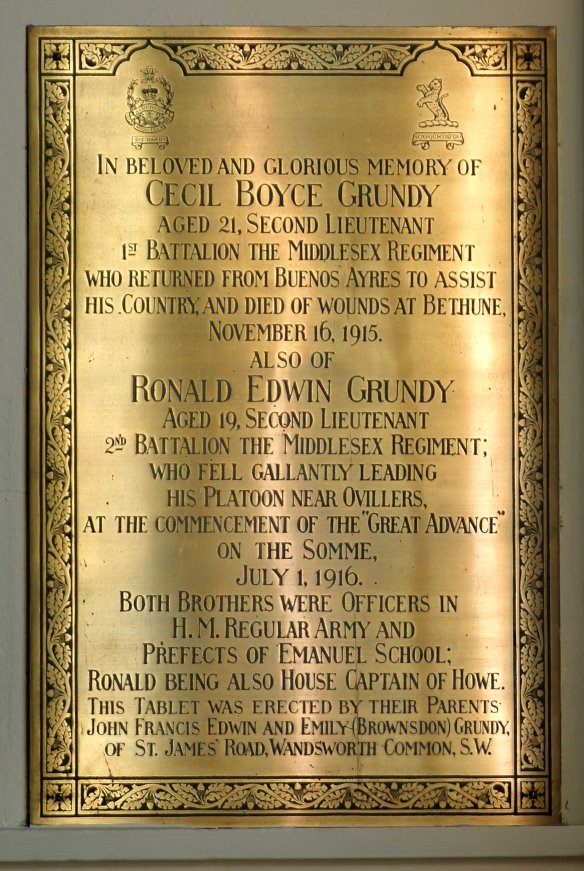

It was the grief over young men like Ronald that eventually claimed the life of another casualty of the first day – Lieutenant-Colonel Edwin Thomas Falkner Sandys, commander of 2nd Battalion Middlesex Regiment. On the first day his battalion, out of any involved in the attack, were given the task of covering the greatest width – some 750 yards – of No Man’s Land. Their objective – the German trenches at the head of Mash Valley. Sandys was concerned before the attack that the artillery bombardment had not achieved its desired effect and that the wire in front of the German trenches was largely in tact. He believed his men would be cut to pieces. It is believed that he made his objections known but no such concern would have stopped the attack at this late stage.

At the end of the first day thirty-one men of the 2nd Battalion are recorded on the Commonwealth War Graves Commission database as having died but Sandys died in September 1916. Sandys had been wounded on the first day and was evacuated to England.

He recovered from his wounds but not his mental torment. The thought that he could have done more for his men plagued him that summer. He wrote two letters which show how his mental state had deteriorated after the attack. In the first, dated 6 September, to Captain Lloyd Jones of the Middlesex Regiment Sandys wrote that he wished he had died with his men on 1 July. He also noted that, ‘I have come to London today to take my life. I have never had a moment’s peace since July 1.’

In the second letter also dated 6 September 1916 addressed to Captain and Adjutant Reginald James Young of 2nd Battalion Middlesex Regiment who had been with Sandys in the 1st July

attack, he wrote, ‘By the time you receive this I shall be dead.’ On the same day as writing the letters Edwin Sandys shot himself in his hotel room at the Cavendish Hotel. Taken to St George’s Hospital he died on 13 September 1916. He is buried in Brompton Cemetery.

The official verdict recorded at an inquest into his death was suicide whilst temporarily insane. He was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Order.

The Officer Commanding “D” Company on 1 July was Captain William James Clachan. Born in Sydney to Scottish parents, William grew up in New Zealand and enlisted at the outbreak of hostilities in 1914. Twice wounded in 1915 he was shot by machine gun fire in his right ankle on the morning of 1 July. He was evacuated to England and on 13 July 1916 whilst recovering in Lady Carnarvon’s Hospital for Officers, 48 Bryanston Square, west London, he wrote to his mother describing that fateful 1 July morning: (Please note the following is an extract from a letter which is copyrighted material)

William Clachan

As for the N.C.O.s I shouldn’t think a company commander could wish for

better and truer soldiers. The men were perfect. There one aim was to get at the bosh. Our half mile advance was down a very gentle slope, immediately in front of the enemy 1st

line was a sunken road in rather a deep little valley. The enemy trenches were on opposite side of this and then up the hill. The whole of this place was swept by the most

cruel machine gun fire. There were at least twenty guns simply pouring lead on us. I have heard machine gun fire before but never such a crackle as that. Every one simply

carried on ahead with a growing hatred for the bosh. There was nothing theatrical about the men, everywhere as they were hit they simply dropped with a silent plunge,

on to their faces. Crumpled up is the correct description. The farther we went the thinner we got. About half way over we ordered the double. By this time in the right half

of our Battalion only the machine gun officer and little me were left of the officers, followed by such a handful of men, probably about fifty, still following grimly. As our

wounded lying about saw us going on many looked up at us smiled and followed even though they were already hit once or twice. Poor fellows they only stopped two or three

more.

I looked at my watch 7.30A.M. Eight minutes exactly and our Battalion was wiped out. … In

writing to or telling anyone else I simply say we walked into hell.

As for Ronald’s fate we know of his last moments leading No. 14 Platoon of “D” Company, 2nd Battalion, Middlesex Regiment from his batman Lance Corporal Walter Noyes. Second Lieutenant Charles Fawcus of “D” Company, a friend of Ronald’s in the Middlesex Regiment and who was in reserve on 1 July, asked Corporal Noyes to write to the Grundys explaining how Ronald died on that fateful morning. Charles Fawcus also wrote to John Grundy on 13 and 23 July 1916 with further details concerning the circumstances of

Ronald’s death.

In a letter dated 13 July to John Grundy, Charles Fawcus mentions that William Clachan was recovering in Lady Carnarvon’s Hospital if he wanted further details about his son’s death but we must assume that John Grundy never contacted William as no letter survives in

either the Clachan or Grundy papers.

Dear Sir,

I wrote you a few days ago and suppose our letters must have crossed. I regret I have been unable to learn anymore than I then wrote, as to his burial place and there is still

heavy fighting going on in that district I collected what belongings of his that I could and handed over to the Quartermaster to be put with his kit and sent home. His

revolver and field glasses were brought in, but I am sorry to say his ring and wrist watch must have been left on him. He showed me a map you sent him of the district we were

in, so you know where he was at the time. I think if you wrote to the Graves’ Registration Committee they would be able to let you have particulars of his burial place. I have heard from Mr Clachan who was his O.C. CO, and is now in Lady Carnarvon’s Hospital for officers, 48 Bryanston Square I am sure he would be very pleased to give you any details he can.

Yours faithfully,

Charles Fawcus.

P.S. Written communications concerning Graves

Registration and Enquiries should be addressed to D. G.

R. AND E. General H/qrs

Letter 23 July, written by Charles Fawcus to Mr Grundy.

Dear Mr Grundy,

I am very sorry to hear you did not receive my first letter. I found what particulars I could of your son’s death, and wrote as soon as I heard, as before we parted he have your

address and asked me to let you know should anything happen to him. I have seen his servant and gained all the information I could from him, and you will no doubt be

glad to hear that he could not have suffered, as his death was absolutely instantaneous, he was over the top leading his men, then started to wave his stick and cheer his men

on, when he must have been sniped as he was hit right through the throat and died at once. His servant carried him back through a sap, but found the entrance filled up with sand bags so had to leave him there. I expect you will be able to get full particulars of where he is buried from the G. R. office, am sorry I do not know any further particulars,

and being in the trenches again now it is difficult to hear much. I have asked Noyes who was your son’s servant to write to you as he was with him all the time. With deepest sympathy to you over your great loss, which is shared by all of us who knew your son,

Yours truly,

Charles G. Fawcus.

P.S. Two parcels arrived for your son, which I distributed as you said.

Lance Corporal Noyes’s letter, 1 August 1916, written to Mr Grundy.

Dear Sir,

I have been requested by Mr Fawcus to give you what information I can concerning the death of Mr Grundy. I was his servant during his brief stay with our company and

was about three feet behind him from the time we left our trench till he was hit. He was killed by a bullet which went in about a quarter of an inch above the collarbone close

up to the neck on the left side and came out through the spine between the shoulder blades. He was dead before he fell and he made no sound, just crumpled up. I dragged him bit by bit until I came to our advanced sap and then I had to leave him so I covered him over with his jacket and brought everything he had that I thought of value and reported him to our Q.M.S. and handed everything to him. Later Mr Fawcus asked if I had seen a ring of Mr Grundy’s

but I never gave it a thought to look for anything of that description, too excited I suppose. I will give you as near as I possibly can where he fell. Draw a line from Ovillers

to Aveluy and make a mark about seven-eighths of the way across from Aveluy and then you will have almost the exact spot. There is one thing you can be assured of

and that is that he was buried properly and his grave is marked as I brought him in and left his identification disc round his neck for that purpose. If there is any further information you require, no matter how slight, I shall be only too pleased to give it you if you will write to L/c W Noyes. D Co 2nd Middlesex Regt. B.E.F. France.

I am yours obediently,

L/c W Noyes.

John Grundy wrote to Walter Noyes with a series of six searching questions concerning Ronald’s death and on 25 August Walter sent his responses. These questions form part of a chorus of desperate fathers’ quests to piece together their beloved sons’ last moments.

Question 1: About how far had my son proceeded after

leaving the trench when he was hit?

Noyes’s Reply: Roughly about nine hundred yards.

Question 2: Do you know if he was wearing his Dayfield

Shield (underneath) and his top boots?

Noyes’s Reply: He was wearing his Dayfield Shield but

not his top boots as they would greatly interfere with the

speed of getting at a wound in the leg or foot.

Question 3: Was he well within sight of the enemy’s snipers

and was there anything about his dress or movements (I

understand he was waving his stick) to be likely to cause

him to be singled out by them.

Noyes’s Reply: It is my opinion that he was shot by an

enemy sniper as, firstly his dress and movements (he was

waving his stick) at once proclaimed him as an officer,

secondly, we were within almost point blank range (about

100 yards), thirdly all M(achine) G(un) and ordinary rifle

fire was much to low to hit him where he was hit.

Question 4: I understand he slept with 14 Platoon in

Ryecroft St on the night of June 30, and that each platoon

slept with its officer in a separate part of the trenches.

Noyes’s Reply: No 14 Platoon occupied four dugouts in

Ryecroft Street, one section to a dugout. Mr Grundy slept

in a dugout occupied by a team of machine gunners as it

was situated with two of his sections’ dugouts on his right

and two on his left.

Question 5: Did he see any of his brother officers on the

morning of the 1st before going over the top?

Noyes’s Reply: Not to my knowledge.

Question 6: I understand that you went over the top at 7.22 am, at about what time was my son shot?

Noyes’s Reply: From the time we left the trench till he was

hit we covered about 900 yds judging that it took us eight

minutes to cover that distance. I could say the time was

7.30 if we, as you say, left the trench at 7.22. I think it was

7.20 but having no watch and not troubling much about

time I am not able to say the exact minute.

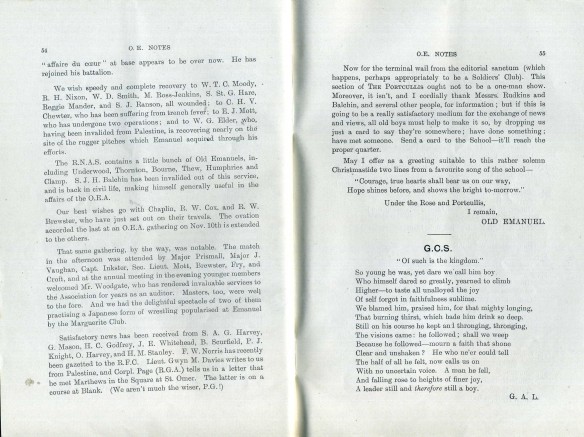

Before he died Ronald asked for money to be left to the Emanuel School chapel

and also requested that a trophy be purchased to, ‘foster the Inter House spirit’. Ronald allocated the sum of twenty pounds to Emanuel. After his death it was his father who carried out the bequest. The following instructions were given to the engravers:

Dear Mr. Hayco

Thanks for yours of the 4th and 8th. Will you please tell me the cost of Chalice 8 ¾ ¨ no 21 in catalogue solid silver with paten plate inscribed round base ‘To the glory of God and the imperishable memory of Ronald Edwin Grundy sometime Prefect of the School, Second Lieutenant 2nd Bn The Middlesex Regiment, who fell near Ovillers July 1 1916 and dying bequeathed this chalice to his School.’

Round the Rim inside (the letters to be filled in with enamel) Drink ye all of this; for this is my Blood of the New Testament, which is shed for you and for many for the remission of sins.

The Grundy Chalice

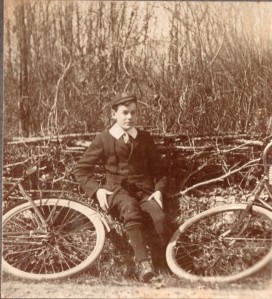

One cannot imagine the thoughts going through John Grundy’s mind as his hand moved the pencil across the piece of paper detailing the memorials to his elder sons (Cecil died at Bethune in November 1915). Within a few years he went from bringing a bicycle home for his sons to play with to considering appropriate words to memorialise them for the School they so loved. He may have sat remembering the camping excursions they so often made each summer, which in one sense were moments from yesterday and in another, a long distant memory viewed from across the fissure in people’s lives created by the First World War.

One point to note is that Ronald’s death was near instantaneous so the words on the chalice, which suggest that he bequeathed it as he lay dying, were, we could assume, an emotive addition created by John perhaps to signify Ronald’s devotion to Emanuel.

Ronald’s death was memorialised in the Christian notions of Sacrifice and Resurrection. The words on the chalice are those associated with the Eucharist. As with Christ, Ronald’s death was not in vain but for a greater cause; he died to save others, ‘for many

for the remission of sins,’ the sin from which a new generation it was hoped would be saved was war. It would appear that by associating Ronald’s death with that of Christ’s sacrifice it brings both meaning to an otherwise incomprehensible loss and also provides a means for the family to work through it, being as they were practicing Christians. It also provides a reminder to the next generation of what these young men fought and gave their lives for.

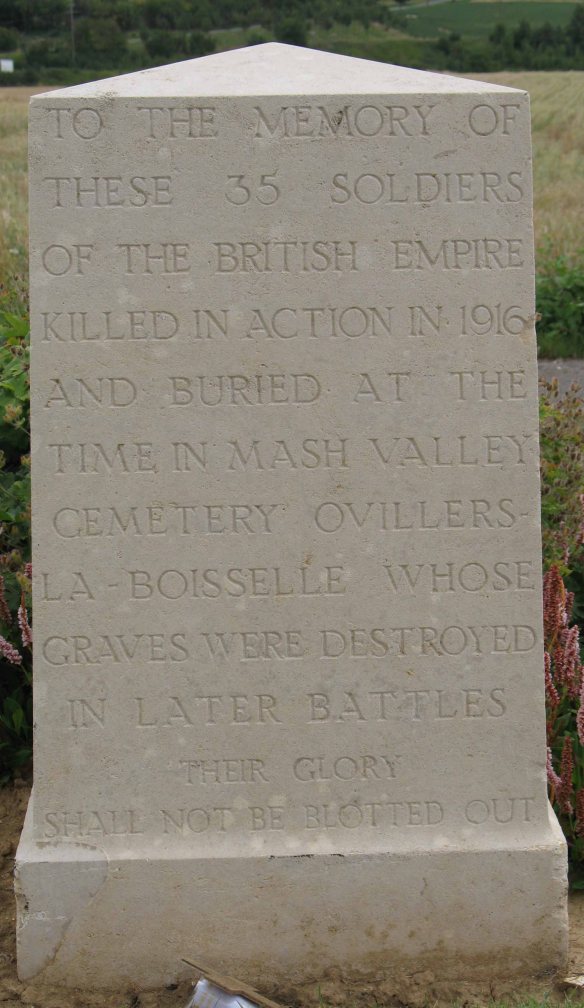

The chalice and paten were accompanied by a memorial plaque which was placed in the “All Souls” side of the School chapel. John requested the plaque from the same engraver and in the same letter he sent to Mr. Hayco.

The Grundy Plaque

The Grundy Cup, as it became known, was the last memorial given to Emanuel in Ronald’s memory. Again, John Grundy noted the details of the words to be engraved on the cup, which was to be instituted as a cup for shooting competitions. The cup was ‘a silver coveredcup surmounted by the figure of a private soldier in the time of the First World War, 1914-18, in full kit with rifle at the slope.’ It bears the School Arms and the inscription:

This Cup Was bequeathed to his School by RONALD EDWIN GRUNDY (sometime Prefect of the School) 2nd Lieutenant in the 2nd B’n The Middlesex Regiment who fell near Ovillers, July 1st, 1916, as a perpetual Trophy for House Competitions In Marching and Shooting.

“Stand fast, brave hearts; what will they say of this in England.”

It was fitting that the first House to win this cup was Howe, Ronald’s old House. In 1935 Mrs Grundy, in the presence of Emanuel School pupils, staff and Mr. John Grundy, presented the cup to Richard Kemp Wildey, who was a Company Sergeant Major in the

OTC and also Captain of Nelson House. Interestingly Richard lived in St James’ Road, the same road on which the Grundys had lived. Richard lost his life when the Halifax he was piloting crashed on the night of 15 October 1942 on a bombing operation on Cologne.

Mrs Grundy presenting the Grundy Cup to Richard Wildey at Emanuel School in 1935

Tomorrow on 1 July 2016 at 7.28am I will be thinking of Ronald and all those young men who went over the top. May we and future generations never forget them – they didn’t get a chance to have a full life – so those of us who do must remember them.

Ronald’s Grave Stone – although he is believed to be buried somewhere near this spot

2nd Lt Ronald Grundy, 2nd Btn Middlesex Regt.

I am hoping to get the Grundy letters published as an ebook – if anyone could help me achieve this goal please get in contact as I lack the funding to achieve it at present.